Gisli Hauksson, RNH Board Chairman, Hannes H. Gissurarson, RNH Academic Director, and Jonas Sigurgeirsson, RNH Managing Director, attended the regional meeting of the MPS, Mont Pèlerin Society, in Seoul in South Korea 7–10 May 2017. The MPS is an international society of classical liberal and conservative scholars and activists founded in Switzerland in April 1947 by Friedrich A. Hayek, Frank H. Knight, Ludwig von Mises, Karl R. Popper, Milton Friedman and others. The speakers in Seoul included Nobel Laureates Vernon Smith and Lars Peter Hansen and renowned economists Professor Israel Kirzner, a specialist on entrepreneurship, and Professor John B. Taylor, after whom the Taylor Rule in banking and finance is named. Dr. Vaclav Klaus, former President of the Czech Republic, and Hwang Kyo-ahn, acting President of Korea, also addressed the meeting. It so happened that the Korean presidential elections took place 9 May, while the meeting was still going on.

Many topics were discussed at the meeting, including growth and inequality, welfare and taxation, the international financial system, Korean security and the Korean economy. Discussions are confidential except people may of course reveal what they say themselves. Hannes H. Gissurarson was commentator on three papers on the Korean economy. He agreed with the lecturers that economic growth in Korea had indeed been spectacular. In early 1960s South Korea was a desperately poor country, but in 2016 its economy was the 11th largest in the world. In 1950, GDP per capita (the usual criterion of wealth) was about 1% of the average in the OECD countries. Then the Korean War broke out and raged for three years, with 1,5 million people being killed and 40% of Korea’s industry being destroyed. But in 1970 Korea’s GDP per capita had risen to 14% of the OECD average, and in 2016 to 85%.

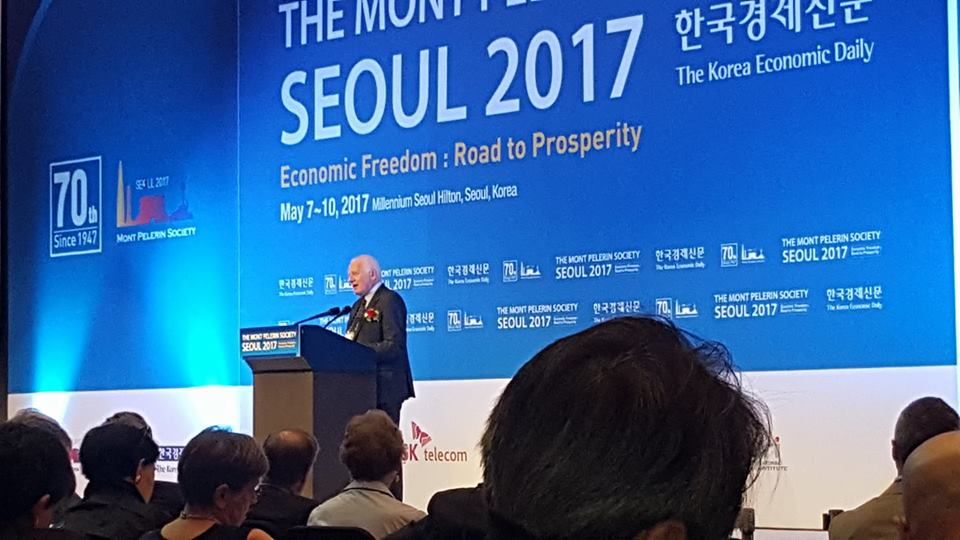

Dr. Ed Feulner of the Heritage Foundation giving a luncheon address on his impressions of Korea over the years.

Gissurarson submitted that the Korean success story had been despite government intervention, but not because of it. He pointed out that relatively small states were often successful because they were homogeneous, with a high level of trust and social cohesion. This was doubtlessly an important factor in the success of the Nordic countries which also all respected the rule of law and free trade. Crucially, their economies had been open. Gissurarson added that bilateral free trade agreements such as those the Koreans were seeking were probably sometimes the least worst option, but that what was desirable was to see an international free trade area, without any tariffs or customs whatsoever. Nations harmed themselves by protecting their domestic production from competition. Free trade agreements could also harm third nations: Korea had for example suffered from a free trade agreement between Mexico and the US.

Sigurgeirsson, Gissurarson and Hauksson. To the right is the logo of the meeting: The two Koreas at night.

The Koreans had, Gissurarson submitted, avoided the great mistake made by many ruling elites in emerging countries of neglecting agriculture. While Korean heavy industry certainly received help in the forms of tax exemptions and cheap credit, a land reform was implemented in Korea creating conditions for efficient food production with modern technology. Moreover, economic intervention in the economy was mostly aimed at encouraging export, but not at protecting domestic companies. The road ahead was, as elsewhere, to abolish discrimination between companies as well as economic sectors and to open up the economy to competition from abroad.

In the discussion about whether to compensate domestic companies for the abolition of tariff protection, Gissurarson recalled when he in Iceland in 1984 introduced a central bank governor to Milton Friedman with the words: “Here is a person, Professor Friedman, who would be out of a job if your recommendations were followed in Iceland.” Friedman was quick to reply: “No, he would not be out of a job: He would just have to move to a more productive job.” Gissurarson said that this was the law of the market. When circumstances changed, people had to move to more productive jobs and more productive sectors of the economy. Undeniably, however, this could be problematic and cause political turmoil, as seemed to be the case now in some Western countries.

Gissurarson discussed another example of an unpopular, but ultimately beneficial increase in productivity. This was moving a factory from a high-pay to a low-pay country. In fact, such a move brought about the redistribution of money from the rich to the poor employees—which presumably should be welcomed by humanitarians. Relatively highly paid people lost one opportunity to sell their services which did not make much of a difference to them, whereas poor people in the receiving country gained an opportunity to better their conditions through hard work. The redistribution taking place was also only in the short term, because in the long term those who lost an opportunity were indirectly compensated by economic growth. As the good produced in the factory now became cheaper than before, a profit was created, to be used to lower the price of the good or to become an addition to the profit of the factory, or both. Whichever was the case, the total supply of goods in society increased.

Gissurarson discussed another example of an unpopular, but ultimately beneficial increase in productivity. This was moving a factory from a high-pay to a low-pay country. In fact, such a move brought about the redistribution of money from the rich to the poor employees—which presumably should be welcomed by humanitarians. Relatively highly paid people lost one opportunity to sell their services which did not make much of a difference to them, whereas poor people in the receiving country gained an opportunity to better their conditions through hard work. The redistribution taking place was also only in the short term, because in the long term those who lost an opportunity were indirectly compensated by economic growth. As the good produced in the factory now became cheaper than before, a profit was created, to be used to lower the price of the good or to become an addition to the profit of the factory, or both. Whichever was the case, the total supply of goods in society increased.

Gissurarson stressed that liberal political leaders had to maintain their support for international free trade. It was still relevant what the Anglo-German politician John Prince Smith observed in the 19th century: If you see a potential customer in someone, your propensity to shoot at him or her diminishes. No less relevant was a comment often attributed to Frédéric Bastiat, but probably first uttered by IBM’s Thomas Watson: If goods cannot cross borders, soldiers will.

![]() Professor Peter Boettke of George Mason University is the President of the Mont Pèlerin Society. The chairman of the programme committee for the Seoul meeting was Professor Pedro Schwartz from Spain, but the three co-chairmen of the local organising committee were Kyu-Jae Jeong, Tae-shin Kwon and Inchul Kim. The next regional meeting will be in Stockholm 2–5 November 2017 about the threat to liberty from increasing populism in the West, followed by a general meeting in the Canary Islands 30 September to 6 October 2018. The participation by the Icelandic guests affiliated with the RNH formed a part in the joint project by RNH and ACRE, the Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe, on “Europe, Iceland and the Future of Capitalism.”

Professor Peter Boettke of George Mason University is the President of the Mont Pèlerin Society. The chairman of the programme committee for the Seoul meeting was Professor Pedro Schwartz from Spain, but the three co-chairmen of the local organising committee were Kyu-Jae Jeong, Tae-shin Kwon and Inchul Kim. The next regional meeting will be in Stockholm 2–5 November 2017 about the threat to liberty from increasing populism in the West, followed by a general meeting in the Canary Islands 30 September to 6 October 2018. The participation by the Icelandic guests affiliated with the RNH formed a part in the joint project by RNH and ACRE, the Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe, on “Europe, Iceland and the Future of Capitalism.”