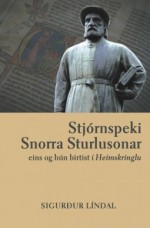

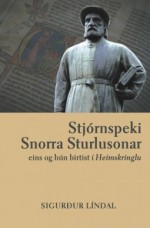

On 23 September 2025, The Icelandic Literary Society (Hid íslenska bókmenntafélag) published an essay by the late Sigurdur Líndal, Professor of Law at the University of Iceland, and widely acknowledged as one of the most learned academics in Iceland in the twentieth century. The title of the 134 pp. essay, originally published in Úlfljótur, the journal of Icelandic law students, in 2007, is ‘Snorri Sturluson’s Political Philosophy as it Appears in Heimskringla’. Snorri Sturluson (1179–1241) is widely believed to be the author of three major works, Edda, the most extensive source on Norse mythology, Heimskringla, a chronicle of the Norwegian kings until the late twelfth century, and The Saga of Egil, the story of a remarkable Icelandic viking-poet. One of the most powerful men of his time in Iceland and twice Lawspeaker, Snorri was killed on 23 September 1241 by one of his rivals, with the consent of the Norwegian king who was angry with Snorri for resisting his attempts to annex Iceland. Davíd Oddsson, former Prime Minister of Iceland, wrote the Foreword to Líndal’s book, while it was edited by RNH Academic Director Hannes H. Gissurarson, Professor Emeritus of Politics at the University of Iceland. It has an English Summary.

On 23 September 2025, The Icelandic Literary Society (Hid íslenska bókmenntafélag) published an essay by the late Sigurdur Líndal, Professor of Law at the University of Iceland, and widely acknowledged as one of the most learned academics in Iceland in the twentieth century. The title of the 134 pp. essay, originally published in Úlfljótur, the journal of Icelandic law students, in 2007, is ‘Snorri Sturluson’s Political Philosophy as it Appears in Heimskringla’. Snorri Sturluson (1179–1241) is widely believed to be the author of three major works, Edda, the most extensive source on Norse mythology, Heimskringla, a chronicle of the Norwegian kings until the late twelfth century, and The Saga of Egil, the story of a remarkable Icelandic viking-poet. One of the most powerful men of his time in Iceland and twice Lawspeaker, Snorri was killed on 23 September 1241 by one of his rivals, with the consent of the Norwegian king who was angry with Snorri for resisting his attempts to annex Iceland. Davíd Oddsson, former Prime Minister of Iceland, wrote the Foreword to Líndal’s book, while it was edited by RNH Academic Director Hannes H. Gissurarson, Professor Emeritus of Politics at the University of Iceland. It has an English Summary.

On the occasion of the publication of Líndal’s book, The Icelandic Literary Society, jointly with the Institute of Medieval Studies at the University of Iceland, the Institute of Law at the University of Iceland, and RSE, the Research Centre for Social and Economic Affairs, held a colloquium at Edda, the house for the ancient Icelandic manuscripts on the University of Iceland campus, on 23 September 2025. Two foreign speakers discussed the contributions of Snorri Sturluson and Sigurdur Líndal to political and legal theory. Ditlev Tamm, Professor Emeritus of Law at the University of Copenhagen, described the old Nordic legal tradition of which Líndal had written much, and pointed out similarities between it and the traditions in many other European countries, for example Hungary. One important principle in that tradition was Quod omnes tangit ab omnibus approbetur (what touches all must be approved of by all) which the American revolutionaries in 1776 interpreted as: no taxation without representation. The question was however how much of the Nordic tradition was really from the Middle Ages, and how much was constructed under the influence of romantic nationalism in the nineteenth century.

Dr. Tom G. Palmer, the International Secretary of Atlas Network, to which almost 600 think tanks around the world belong, also discussed the significance of the principle Quod omnes tangit ab omnibus approbetur, which was, he argued, one of the most important pillars of modern democracy. It was given a pithy form, he said, in the Polish-Lithuanian Republic of Nobles, Nic o nas bez nas (Nothing about us, Without Us). Palmer also mentioned the reflections on politics by Cicero in his book On Duty which showed, he suggested, some striking similarities with the famous speech by the Icelandic farmer Einar of Thverá in Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla, where Einar points out that kings turn out differently, some well and some badly, so it was necessary to constrain their power, especially their power to tax and to engage in warfare.

Gudlaugur Thór Thórdarson, fmr. Foreign Minister, Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, fmr. President of Iceland, and Prof. Hannes H. Gissurarson at the reception following the meeting.

A lively discussion followed the two papers. Lilja Alfredsdóttir, former Minister of Education, recalled the description by Tacitus in Germania about the self-government of the German tribes which seemed very similar to the system of the Icelandic Commonwealth. Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson, the former President of Iceland, emphasised the Germanic heritage of the Nordic and Anglo-Saxon nations which had been particularly relevant in Snorri Sturluson’s time when it had come into conflict with the attempts by the Norwegian kings to establish centralised power, under the influence of ideas from the south of Europe. This Nordic and Anglo-Saxon heritage had again become relevant in our time, Grímsson said, when attempts were being made to establish centralised power in Brussels. Gudni Ágústsson, former Minister of Agriculture, pointed out that Snorri Sturluson had been brought up in the famous site of learning Oddi, and that perhaps he had something to do with the writing of Njal’s Saga, in Gudni’s opinion the best Icelandic saga. Hannes H. Gissurarson who led the discussion responded that Snorri had written Egil’s Saga which was very anti-royalist in spirit, but that possibly his nephew, the historian Sturla Thordarson, had written Njal’s Saga which was not at all hostile to royalty. The difference between Snorri and Sturla had been that Snorri wanted to maintain the independence of Iceland, which she had enjoyed for three centuries, whereas Sturla was very much the king’s man.

The meeting hall at Edda was packed. The meeting was chaired by Gardar Gíslason, former Supreme Court Justice, whereas the publication of Líndal’s book was supported by RSE, the Icelandic Centre for Social and Economic Research. After the meeting, RSE hosted a reception at the premises, and in the evening it invited the speakers and organisers of the event to dinner. From left: Haraldur Bernhardsson, Director of the University of Iceland Institute of Medieval Studies, María Jóhannsdóttir, widow of Prof. Sigurdur Líndal, Prof. Ditlev Tamm, Prof. Anna Agnarsdóttir, Sigurgeir Orri Sigurgeirsson, who designed the book, Elisa Eyvindsdóttir, editor of Úlfljótur, Prof. Hannes H. Gissurarson, Prof. Ragnar Árnason, Dr. Tom G. Palmer, Gardar Gíslason, fmr. Supreme Court Justice, and Salka Sigmarsdóttir, editor of Úlfljótur.

The day before the colloquium, Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson published an article in Morgunbladid, Our Contemporary, Snorri Sturluson, where he argued that Snorri’s ideas were still relevant: government by consent, the right of rebellion (now interpreted as the right regularly to vote those in power out of office), no taxation without representation and a foreign policy that the Icelandic nation should be the friend of all, but the subject of none.

RNH Academic director, Hannes H. Gissurarson, Professor Emeritus in Politics at the University of Iceland, was the guest of honour at the annual Thjodmal Gala Dinner on 20 November where awards were given to innovative business leaders. The Whale Museum in Reykjavik was the venue of the event, which was attended by 270 guests. The choir Fostbraedur sang a few patriotic Icelandic songs, and the popular singers Eyjolfur Kristjansson, Stefan Hilmarsson, and Bergthor Palsson also performed. Gisli F. Valdorsson, who runs the Thjodmal podcast, delivered some opening remarks while the master of ceremonies, journalist Stefan Einar Stefansson, mocked the enthusiasm for raising taxes by the present Icelandic government. In his short speech, Professor Gissurarson told a few anecdotes about himself, Prime Ministers Bjarni Benediktsson and David Oddsson, Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises, and his left-wing colleagues in the Faculty of Politics at the University of Iceland who had been less than happy when he was appointed Professor in the Summer of 1988. Gissurarson recalled a lot of comical incidents at faculty meetings. He found it fitting that this dinner was at the Whale Museum because he, like the whales, migrated during the coldest and darkest months of the year from Iceland to the southern hemisphere. Gissurarson also quoted humorous observations about alcohol by Icelandic wits such as poet Tomas Gudmundsson and lawyer Jon E. Ragnarsson.

RNH Academic director, Hannes H. Gissurarson, Professor Emeritus in Politics at the University of Iceland, was the guest of honour at the annual Thjodmal Gala Dinner on 20 November where awards were given to innovative business leaders. The Whale Museum in Reykjavik was the venue of the event, which was attended by 270 guests. The choir Fostbraedur sang a few patriotic Icelandic songs, and the popular singers Eyjolfur Kristjansson, Stefan Hilmarsson, and Bergthor Palsson also performed. Gisli F. Valdorsson, who runs the Thjodmal podcast, delivered some opening remarks while the master of ceremonies, journalist Stefan Einar Stefansson, mocked the enthusiasm for raising taxes by the present Icelandic government. In his short speech, Professor Gissurarson told a few anecdotes about himself, Prime Ministers Bjarni Benediktsson and David Oddsson, Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises, and his left-wing colleagues in the Faculty of Politics at the University of Iceland who had been less than happy when he was appointed Professor in the Summer of 1988. Gissurarson recalled a lot of comical incidents at faculty meetings. He found it fitting that this dinner was at the Whale Museum because he, like the whales, migrated during the coldest and darkest months of the year from Iceland to the southern hemisphere. Gissurarson also quoted humorous observations about alcohol by Icelandic wits such as poet Tomas Gudmundsson and lawyer Jon E. Ragnarsson.