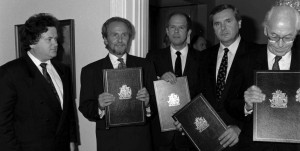

26 August 1991: Prime Minister Oddsson with the foreign ministers of Iceland and the Baltic countries.

Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson delivered a paper 25 October 2013 on “Different Nations — Shared Experiences: Iceland and the Baltic Countries” in a seminar on the international angle at the annual conference “The Mirror of the Nation” where teachers at the School of Social Sciences at the University of Iceland present their research. He pointed out that Iceland and the three Baltic countries all gained sovereignty the same year, in 1918. All four countries were occupied in the spring of 1940, Iceland by the British, and the Baltic Countries by Stalin’s Red Army. In all four countries, military control passed to another state in the summer of 1941: Iceland made a defence treaty with the United States, and the German Army occupied the Baltic countries, driving out the Red Army. The year 1944 had also been significant in all four countries, Iceland becoming a republic, and the three Baltic countries being forced to re-enter the Soviet Union where they had been briefly, and nominally, member-states before the German occupation.

From the outset, the history of the international communist movement was linked to the history of those four small countries. Professor Gissurarson gave a brief account of the history of the Icelandic communist movement which started when Brynjolfur Bjarnason and Hendrik Ottosson became Bolshevik supporters after street riots in Copenhagen in 1918, and went on to become delegates to the Comintern Congress in Moscow in 1920. In 1923, a Latvian Jewess, Liba Fridland, gave lectures in Iceland about the Bolshevik Revolution, with Ottosson vehemently protesting in the organ of the Social Democratic Party (where the communists operated until 1930 when they founded the Communist Party under orders from Moscow). Professor Gissurarson also described a controversy in 1945–1946 about the situation in the Baltic countries between the conservative newspaper Morgunbladid and the socialist organ Thjodviljinn. A Lithuanian refugee, Teodoras Bieliackinas, had written about the Soviet oppression of the Baltic countries, with the result that the socialist organ called him a “Lithuanian fascist”. By then, the Communist Party had been dissolved, but the Socialist Party replacing it in 1938 also strongly supported the Soviet Union.

Professor Gissurarson mentioned the 1955 foundation of the Open Book Club, the Almenna bokafelagid, which was to resist the communist dominance of Icelandic cultural life. Its first publication was Baltic Eclipse by Estonian Literature Professor Ants Oras. In the summer of 1957, the Icelandic President, Asgeir Asgeirsson—a staunch anti-communist—and Foreign Minister Gudmundur I. Gudmundsson received Dr. August Rei, Prime Minister of the Estonian government-in-exile in Stockholm, at the President’s residence, after which the Soviet Ambassador, Pavel Ermoshin, protested formally. In 1973, the Open Book Club published Estonia. A Small Nation Under Foreign Yoke by Andres Küng, an Estonian-Swedish journalist and writer. The book was translated into Icelandic by a law student at the University, David Oddsson. By this time, most leftists in Iceland had turned their back on the Soviet Union, even if some of them maintained ties with Cuba and China. On the far left, the People’s Alliance had replaced the Socialist Party. In 1991, when Iceland became the first country to re-recognise the independence of the Baltic countries, Oddsson was Prime Minister.

Finally, Professor Gissurarson presented the findings of a survey that he did with his student, Helena Ros Sturludottir, on the treatment of Baltic history in Icelandic textbooks. In particular, Professor Gissurarson criticized the widely-used textbook Modern Times (Nyi timinn) by two socialist historians, Gunnar Karlsson and Sigurdur Ragnarsson. In this book, the fact is not really mentioned that the Baltic countries were occupied by the Red Army in 1940; instead it is said that they were “annexed” by the Soviet Union, becoming Soviet republics. It is also said that the Western powers at Yalta de facto recognised Soviet control of the Baltic states. According to Professor Gissurarson, this was highly debatable, the main point surely being that the democratically-elected Western leaders and the Eastern dictator used the concept of a “sphere of influence” in different senses. Furthermore, in the book by Karlsson and Ragnarsson it is said that the Baltic countries in 1991, under the influence of growing nationalism, used their right under the Soviet constitution to secede from the Soviet Union. This was not relevant, Professor Gissurarson responded. If the Baltic countries did in fact have this right, why did they not secede much earlier, given the unpopularity of the Kremlin masters in those countries? It was clear that the Baltic countries had never freely joined the Soviet Union. Their status in 1940 to 1991, under international law, was that of occupied countries, not that of fully recognised Soviet republics.

The lecture of Professor Gissurarson forms a part of the joint project by RNH and AECR, the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists, on “Europe of the Victims: Remembering Communism”. He also co-operated with institutes in Estonia and Latvia working on the project “Different Nations — Shared Experiences”.