25 October 2013, Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson read a paper at a seminar on the 2008 Icelandic bank collapse, a part of the annual conference “The Mirror of the Nation” where social scientists at the University of Iceland present their recent research. Professor Gissurarson rejected two common explanations of the bank collapse. One of them was that, under the influence of “neo-liberalism”, Iceland had deregulated the financial market. Gissurarson pointed out that Iceland operated under precisely the same legal and regulatory framework for the financial market as other member-states of the EEA, European Economic Area, which Iceland joined in 1994. The second explanation was that Icelandic bankers were more reckless than bankers elsewhere. Gissurarson pointed out that they had been able to find customers, both depositors and creditors, who would then have been guilty of the same recklessness. But, Gissurarson submitted, there were nevertheless two systemic risks to be found in the Icelandic banking sector. One was extensive cross-ownership and excessive borrowing by one business group — clearly identified and explained in the report by Parliament’s Special Investigation Commission on the bank collapse. The other additional systemic risk was the enormous difference between the banks’ field of operations — all of Europe — and their field of institutional support — Iceland alone, as it turned out.

25 October 2013, Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson read a paper at a seminar on the 2008 Icelandic bank collapse, a part of the annual conference “The Mirror of the Nation” where social scientists at the University of Iceland present their recent research. Professor Gissurarson rejected two common explanations of the bank collapse. One of them was that, under the influence of “neo-liberalism”, Iceland had deregulated the financial market. Gissurarson pointed out that Iceland operated under precisely the same legal and regulatory framework for the financial market as other member-states of the EEA, European Economic Area, which Iceland joined in 1994. The second explanation was that Icelandic bankers were more reckless than bankers elsewhere. Gissurarson pointed out that they had been able to find customers, both depositors and creditors, who would then have been guilty of the same recklessness. But, Gissurarson submitted, there were nevertheless two systemic risks to be found in the Icelandic banking sector. One was extensive cross-ownership and excessive borrowing by one business group — clearly identified and explained in the report by Parliament’s Special Investigation Commission on the bank collapse. The other additional systemic risk was the enormous difference between the banks’ field of operations — all of Europe — and their field of institutional support — Iceland alone, as it turned out.

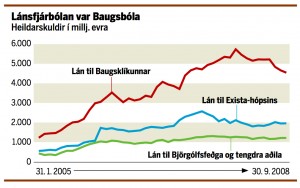

Professor Gissurarson displayed a graph which he had drawn with figures from the report of the Special Investigation Commission about the total borrowing in Icelandic banks by the three dominant business groups in Iceland before the collapse. It is clear from that graph that the Baugur Group and their associates were quite distinct in this respect. However, what was crucial for the collapse was that into this already vulnerable situation entered three decisions made abroad. One was the refusal of the American Federal Reserve System to make currency swap deals with the Icelandic Central Bank, at the same time as it made such deals with the other Nordic central banks and in fact with all central banks in the Western world, outside the Eurozone. A second decision was that of the British Financial Supervisory Authority to close the two London banks owned by Icelanders at the same time—indeed, the very same day—as it offered all other banks in Britain a generous rescue package. The third decision was that of the British Treasury to invoke the British anti-terrorism law against an Iceland bank, with repercussions not only for that bank, but also for the whole Icelandic financial system. The subsequent sale of Icelandic assets fetched much less than reasonable prices, even in an international financial crisis. Professor Gissurarson gave a few examples from Norway. His paper formed a part of a joint project by RNH and AECR, the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists, on “Europe, Iceland and the Future of Capitalism”.