In September 2010, a narrow majority in the Icelandic Parliament decided to impeach Geir H. Haarde, Iceland’s Prime Minister in 2006–9 and Leader of the centre-right Independence Party, for negligence in the period leading up to the 2008 bank collapse. It was decided, also by small majorities, not to impeach three other former leading government ministers although a left-wing majority in a special parliamentary review committee had recommended it. The committee’s recommendations had been based on a long report on the bank collapse by a Special Investigation Commission, SIC, with three members, a Supreme Court judge, the Parliamentary Ombudsman, and a recent graduate in finance teaching at Yale at the time. In April 2012, the Impeachment Court passed its judgement on the six charges against Haarde. It had already dismissed two charges, and now it unanimously acquitted him of three charges, whereas a majority of nine found him guilty of only one charge: that of not having held cabinet meetings about the impending bank collapse as required by the Icelandic Constitution; a minority of six, including two Supreme Court judges, also wanted to acquit him on this count.

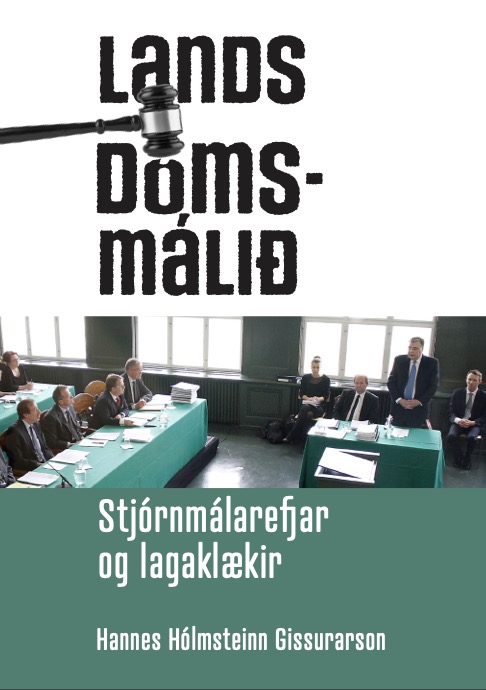

The whole process was quite controversial in Iceland, not least because most people thought that Geir H. Haarde himself should not be the only Icelandic politician in office before the bank collapse to be held responsible. In a new book of 366 pages in Icelandic, The Impeachment Case: Political Machinations and Legal Maneuvers (Landsdomsmalid: Stjornmalarefjar og lagaklaekir), RNH Academic Director Hannes H. Gissurarson, Professor of Politics at the University of Iceland, argues that the whole process was unjust and that Haarde’s conviction on the somewhat trivial charge of not having held cabinet meetings about the impending bank collapse was legally groundless. The 1920 constitutional stipulation that cabinet meetings had to be held about all ‘important government issues’ was derived from the fact that Iceland was then a kingdom in a personal union with the Danish king who resided in Copenhagen. Twice a year an Icelandic government minister went to Copenhagen to attend the Icelandic Council of State with the king and the crown prince where he presented not only his own issues but also those of other ministers. Thus, it had to be ensured that all these issues had already been properly discussed at cabinet meetings. When Iceland became a republic in 1944, the constitutional stipulation about cabinet meetings was interpreted as a requirement to discuss all issues at cabinet meetings that subsequently were to be presented in the rarely-held Council of State, presided over by the president.

The whole process was quite controversial in Iceland, not least because most people thought that Geir H. Haarde himself should not be the only Icelandic politician in office before the bank collapse to be held responsible. In a new book of 366 pages in Icelandic, The Impeachment Case: Political Machinations and Legal Maneuvers (Landsdomsmalid: Stjornmalarefjar og lagaklaekir), RNH Academic Director Hannes H. Gissurarson, Professor of Politics at the University of Iceland, argues that the whole process was unjust and that Haarde’s conviction on the somewhat trivial charge of not having held cabinet meetings about the impending bank collapse was legally groundless. The 1920 constitutional stipulation that cabinet meetings had to be held about all ‘important government issues’ was derived from the fact that Iceland was then a kingdom in a personal union with the Danish king who resided in Copenhagen. Twice a year an Icelandic government minister went to Copenhagen to attend the Icelandic Council of State with the king and the crown prince where he presented not only his own issues but also those of other ministers. Thus, it had to be ensured that all these issues had already been properly discussed at cabinet meetings. When Iceland became a republic in 1944, the constitutional stipulation about cabinet meetings was interpreted as a requirement to discuss all issues at cabinet meetings that subsequently were to be presented in the rarely-held Council of State, presided over by the president.

In his book, Gissurarson argues that three venerable legal principles had been violated in the impeachment process against Geir H. Haarde. The principle Nullum poena sine lege, no conviction without law, was violated by the SIC which had based its accusations of Haarde’s negligence on a law passed at the end of 2008, after the bank collapse, thus applying the law retroactively. The principle Ne bis in idem, not again, or double jeopardy, was violated by the parliamentary review committee when it added the charge on cabinet meetings to other accusations of negligence against Haarde, because the SIC had already considered this particular charge and dismissed it. The principle In dubio, pars mitior est sequenda, when in doubt, choose the milder course, was violated by the majority of the Impeachment Court when it used a controversial and doubtful interpretation of the constitutional stipulation about cabinet meetings to convict Haarde on a fairly trivial issue. Gissurarson suggests that the majority simply wanted to respond to the loud popular demand after the collapse for a scapegoat. He points out, also, that before the collapse it would indeed have been unwise to hold cabinet meetings on the problems of the struggling banks, thus bringing unwelcome attention to them, and that in the past cabinet meetings had not been held on some sensitive yet important issues, such as negotiations in 1956 on defence arrangements with the United States while communists were participating in a coalition government and the 2003 declaration of support for the Iraq War made jointly by the then prime minister and the foreign minister.

Feelings ran high during the bank collapse. Haarde’s car was attacked by an angry mob on 21 January 2009 while he was still Prime Minister.

It was not negligence by government ministers which turned a foreseeable bank crisis in Iceland into a bank collapse, Gissurarson argues. It was a series of events which together formed a ‘black swan’, a sudden, unexpected incident which could only be foreseen by the knowledge gained by its very passing. In his book, Gissurarson lists 12 events that combined together to bring about the collapse, including the refusal of the U.S. Fed to offer to the Central Bank of Iceland the same dollar swap deals that it made with the three Scandinavian central banks and the refusal of the British government to offer to the two British banks owned by Icelanders the same liquidity provisions it made available to all other British banks. Gissurarson also points out that three judges on the Impeachment Court—who all voted for conviction on the cabinet meeting charge—had themselves lost a lot of money in the bank collapse, both bank stocks and money kept in money market funds and that they could therefore be seen as holding a possible grudge against former Prime Minister Haarde who had refused to bail out the banks. One of them, Eirikur Tomasson, had not only had a considerable financial interest in the fallen banks, but he had also blamed the collapse partly on Haarde in a 2009 article on the internet which mysteriously disappeared before he took a seat on the Court, while the same judge had protested loudly when Haarde had not appointed him Supreme Court judge in 2004. Tomasson certainly should have recused himself, Gissurarson says.

Gissurarson first presented his book (which carries an English Summary) on 4 December in Silfrid, a television programme on current affairs at the National Broadcasting Service. He was interviewed in Dagmal, a television programme operated by the newspaper Morgunbladid, on 7 December, in Hrafnathing, a small private right-wing television station, on 9 December and in Hringbraut, a television programme operated by the newspaper Frettabladid, on 12 December. He also discussed his book in two popular podcasts, by Solvi Tryggvason 10 December and Thorarinn Hjartarson 17 December, and at the private radio station Utvarp Saga on 16 December. A long comment on some issues in Gissurarson’s analysis of the impeachment case, in particular the incompetency of one of the judges, was published in the web journal Visir on 8 December. A business weekly, Vidskiptabladid, published an extract from the book on 15 December. Gissurarson shares some of his findings in the case with the readers of Morgunbladid in his weekly column on Saturdays, and in an article in the left-wing journal Stundin on 21 December. On 8 December, at a large party given by the Public Book Club which publishes Gissurarson’s book, the author gave a copy to former Prime Minister Haarde who in a short address thanked Gissurarson for his initiative. At the party, a former member of parliament for the Independence Party, the Reverend Hjalmar Jonsson, recited to general merriment a few humorous verses he had composed about the book and the case itself, widely seen in Iceland as a travesty of justice. Here is an account in Morgunbladid on 9 December about the party: