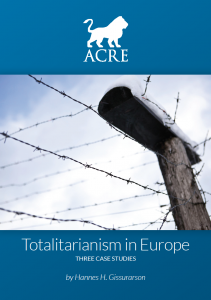

The 20th century was the best of times, and it was the worst of times, Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson, RNH Academic Director, said in a talk at the University of Iceland 26 April 2018. It was a time of prosperity and progress, but also of totalitarian mass murders, by Nazis and communists. It is estimated that about 120–125 million people lost their lives because of totalitarianism in the 20th century, but the lives of many more people were affected and abrogated. The occasion for Gissurarson’s talk was the recent publication of his Totalitarianism in Europe: Three Case Studies, written at the initiative of ACRE, Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe, as a part of the joint project with RNH, ‘Europe of the Victims’.

Gissurarson first told the story of Elinor Lipper, a young and intelligent girl of Jewish origin who became a communist and a Comintern courier all over Europe, also briefly having an affair with Italian writer Ignazio Silone. She went to Russia in 1937, but then Stalin’s purges were at their worst, and she was to spend the next eleven years in labour camps. She was a Swiss citizen, and because of the persistence of Swiss authorities she was released in 1948, after which she wrote a book about her experience that sold quite well and was much-discussed. Extracts of the books were published in Icelandic newspapers Timinn and Visir, and the one in Visir has been republished. In his research, Gissurarson discovered many unexpected facts about Lipper.

Then Gissurarson gave an account of a surprise encounter at the 60 years birthday party in Iceland of communist leader Brynjolfur Bjarnason in May 1958. A Jewish lady attending the party, Henny Goldstein, who had fled from Hitler to Iceland in 1934 suddenly noticed there a German Nazi whom she had known in Iceland before the war, Dr. Bruno Kress. She protested against his presence, but the incident was hushed down. During the war, Henny’s brother, Siegbert Rosenthal, and her sister-in-law and nephew, were sent to Auschwitz only a month before Henny and her husband had provided the necessary permissions for living outside Germany. The wife and the son were murdered almost immediately by the Nazis, but Rosenthal was selected to participate in the ‘skeleton collection’ of the Ahnenerbe, the SS ‘research institute’ and subsequently murdered. In Iceland, Dr. Kress was on a grant from the same Ahnenerbe, to write an Icelandic grammar. He was then a Nazi, but after the war he became a communist and the director of the Nordic Institute at Greifswald University, whereas the Director of Ahnenerbe was hanged for war crimes. Kress received an honorary doctorate from the University of Iceland in 1986.

Finally Gissurarson turned to the most prominent Stalinist apologist in Iceland, the writer Halldor K. Laxness. In the 1930s, he wrote two travel books about the Soviet Union, but decades later he admitted that there he had not told the truth. In his later trip to the Soviet Union, in 1937–8, he had attended the public trial of Bukharin and his comrades whom Stalin forced to confess to the most extraordinary misdeeds. During the same trip, Laxness had also witnessed the arrest of an innocent young woman at her home, Vera Hertzsch, who had had a child with an Icelandic student in Moscow. Hertzsch was a German communist living in Russia and previously had been married to an alleged ‘Trotskyite’.

Finally Gissurarson turned to the most prominent Stalinist apologist in Iceland, the writer Halldor K. Laxness. In the 1930s, he wrote two travel books about the Soviet Union, but decades later he admitted that there he had not told the truth. In his later trip to the Soviet Union, in 1937–8, he had attended the public trial of Bukharin and his comrades whom Stalin forced to confess to the most extraordinary misdeeds. During the same trip, Laxness had also witnessed the arrest of an innocent young woman at her home, Vera Hertzsch, who had had a child with an Icelandic student in Moscow. Hertzsch was a German communist living in Russia and previously had been married to an alleged ‘Trotskyite’.

Gissurarson then tried to explain why so many prominent 20th century intellectuals supported totalitarianism, bitterly rejecting the system of free competition and private property. Schumpeter had suggested that intellectuals were alienated from society and that they usually lacked experience in making things works. Mises had surmised that intellectuals expected to do better personally under socialism than capitalism. Jouvenel had pointed out that intellectuals seemed to abhor having to produce in order to satisfy the needs of others, as the market system requires. Hayek had observed that many intellectuals could not envisage the spontaneous evolution that takes place under capitalism: They thought that everything had to be designed by human reason. Gissurarson found all of these explanations to fit Laxness, but especially the last one.

Gissurarson then tried to explain why so many prominent 20th century intellectuals supported totalitarianism, bitterly rejecting the system of free competition and private property. Schumpeter had suggested that intellectuals were alienated from society and that they usually lacked experience in making things works. Mises had surmised that intellectuals expected to do better personally under socialism than capitalism. Jouvenel had pointed out that intellectuals seemed to abhor having to produce in order to satisfy the needs of others, as the market system requires. Hayek had observed that many intellectuals could not envisage the spontaneous evolution that takes place under capitalism: They thought that everything had to be designed by human reason. Gissurarson found all of these explanations to fit Laxness, but especially the last one.

![]() The meeting was well-attended. While historian Bessi Johannsdottir chaired it, Dr. Dalibor Rohac, analyst of Central and Eastern European affairs at the American Enterprise Institute, was commentator. Rohac recalled that he was born in a communist country with barbed wire and watchtowers visible from his parents’ house in Bratislava. The stories Gissurarson told were tragic, but needed to be remembered, Rohac said. Guests at the meeting included Tomas Ingi Olrich, former Minister of Education, and History Professor Thor Whitehead, Iceland’s leading expert on communism, both of whom joined in the discussion after the talk.

The meeting was well-attended. While historian Bessi Johannsdottir chaired it, Dr. Dalibor Rohac, analyst of Central and Eastern European affairs at the American Enterprise Institute, was commentator. Rohac recalled that he was born in a communist country with barbed wire and watchtowers visible from his parents’ house in Bratislava. The stories Gissurarson told were tragic, but needed to be remembered, Rohac said. Guests at the meeting included Tomas Ingi Olrich, former Minister of Education, and History Professor Thor Whitehead, Iceland’s leading expert on communism, both of whom joined in the discussion after the talk.