RNH Academic Director, Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson, gave a talk at a Reykjavik luncheon meeting of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs 16 June 2016. It formed a part of the joint project of RNH and AECR, Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists, on “Europe, Iceland and the Future of Capitalism”. Here are the main points of the talk:

RNH Academic Director, Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson, gave a talk at a Reykjavik luncheon meeting of the Chicago Council on Global Affairs 16 June 2016. It formed a part of the joint project of RNH and AECR, Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists, on “Europe, Iceland and the Future of Capitalism”. Here are the main points of the talk:

Determinants of Iceland’s Foreign Policy: 1) tiny nation which cannot defend herself; 2) far from being self-sufficient, need for markets; 3) location in mid-North Atlantic Ocean, immediate neighbours Norway, Great Britain, Canada, the US, 4) culturally part of the West and the North

874 First settler from Western Norway, most settlers from Norway

930 Foundation of Commonwealth, the rule of law without government

1000 Discovery of America, oral tradition confirmed by archeological findings

1022 First treaty with Norwegian king, mutual rights

1262 Covenant reluctantly made with Norwegian king: dependency or tributary state

1355–1374 Ruled by the King of Sweden, not Norway (shows tenuous links with Norway)

1380 Ruled by the King of Denmark, as Norway and Denmark enter a personal union

1412 First recorded English fishing vessel; becomes an important part of English fisheries

Henry VIII refused three offers to buy Iceland

1518 Danish king offered Iceland to Henry VIII as collateral for 50,000 gold florins loan (=$6.5 million). Two more offers, in 1524 and 1535

1490–1602 Consolidation of royal prerogatives in Iceland; foreigners excluded, monopoly trade

1627 Uselessness of Danish “shelter” exposed: Muslim raids without any defence

1645 Danish king offered Iceland to Hamburg merchants for 500,000 thalers (=$6.4 million).

1785 Danish officials seriously discuss evacuating the Icelanders to other parts of the realm, as a result of volcanic eruptions, earthquakes and the “Mist Famine”

1785–1813 Several suggestions by British individuals that the UK seize Iceland; little interest

1814 Iceland not included when Sweden gets Norway as compensation for Finland. Why? Probably decision by the UK: Wanted Iceland controlled by a weak power, but had no interest in ruling her directly, tacit protection in the following century by British Navy

Jon Sigurdsson, leader of Iceland’s independence struggle

1848 Jon Sigurdsson calls for self-rule and sovereignty, using three arguments: 1) Iceland always sovereign; 2) Distinct culture and language; 3) Local knowledge

1855 Freedom of trade

1868 US government plans to purchase Iceland from Denmark, like Louisiana from France and Alaska from Russia; proponents William H. Seward and Robert J. Walker; laughed out of Congress

1876 last year when export of agricultural products exceeds that of marine products in value

1914–1918 UK government practically takes over Iceland, British consul controls foreign trade; direct trade negotiations between the UK and Iceland (still a Danish dependency); uselessness of Danish “shelter” demonstrated yet again

1918 Denmark grants Iceland sovereignty, independent kingdoms in personal union

1940 UK occupies Iceland

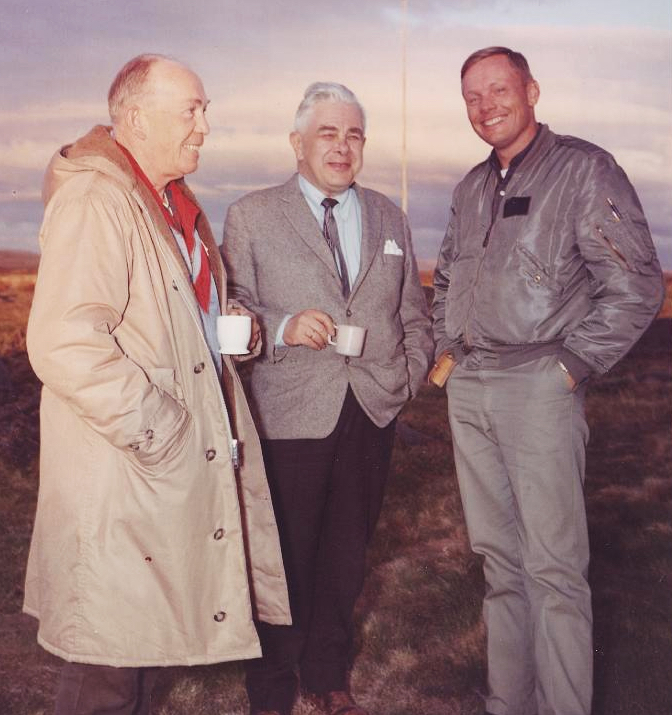

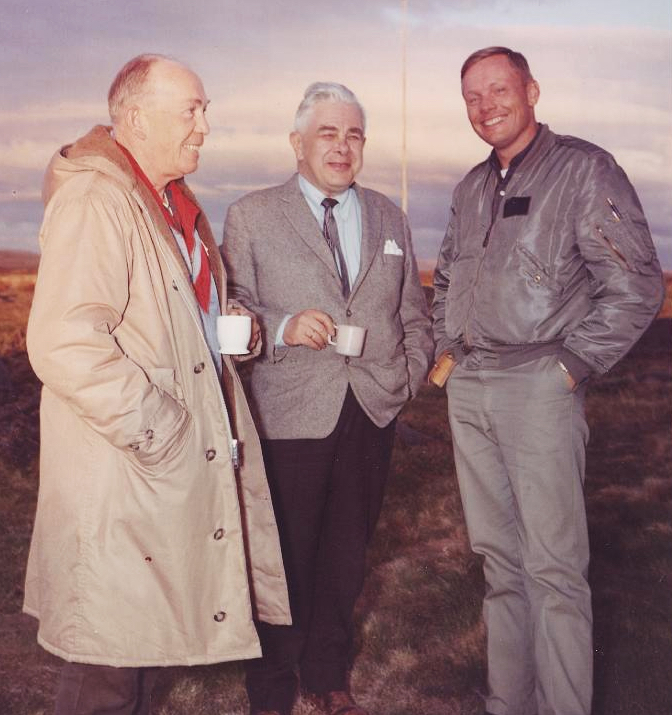

Iceland 1967: US Ambassador Karl Rolvaag, Icelandic Prime Minister Bjarni Benediktsson (who signed the North Atlantic treaty in 1949 and the Defence Treaty with the US in 1951) and astronaut Neil Armstrong, training for his journey.

1941 US and Iceland conclude a defence agreement, Monroe line drawn east of Iceland, Churchill visits

1949 Iceland joins NATO, strategically important in Cold War

1951 Defence Treaty with US, still in force

1952–76, four extensions of fisheries limits, Cod Wars with the UK, tacit support by the US

2006 US unilaterally abandons military base in Iceland

2008 Iceland left out in the cold, no help from US which however helps Switzerland and Sweden (never allies); severe blow from UK government, closing British banks owned by Icelanders while assisting all other British banks; putting an Icelandic bank and, briefly, also Central Bank and Finance Ministry on list of terrorist organisations; contributes to total collapse

2009 Disillusioned with old friends and allies, majority of Parliament decides to apply for EU membership; but “negotiations” stall: Iceland’s fisheries well-run, CFP disaster

2006–16 Iceland alone, expendable, unwanted, unprotected (except by US and NATO declarations), as in 1518–1868

Two future options, North Atlantic or European; not mutually exclusive. Terms:

1) continued access to European market, but also trade with US, Canada, China, Russia, etc.

2) continued independent currency, but deal with the UK or US on convertibility and lender-of-last-resort facilities (permanent currency swap deals)

3) rejuvenated military cooperation with US, adding UK and Norway to the equation

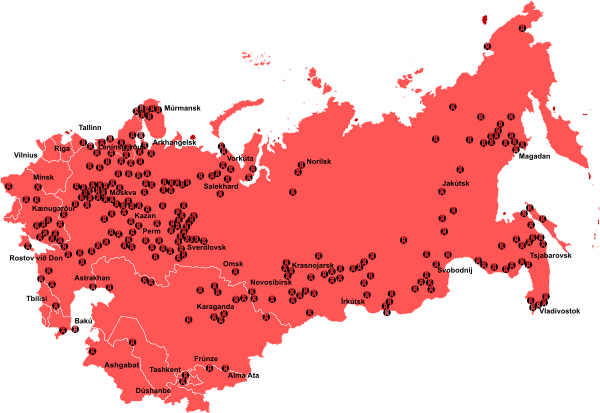

On 17 July 2016, 80 years had passed since the Spanish Civil War broke out when nationalist generals led by Francisco Franco rebelled against the young Spanish Republic. On this occasion, AB, the Public Book Club, republished the book El Campesino by Valentín González and Julián Gorkin. It is accessible online and also in print. González, El campesino, a general in the Spanish Republican Army, was often featured on the front pages of the Icelandic communist party organ Thjodviljinn, appearing as well as one of the characters in Ernest Hemingway’s famous novel on the Spanish Civil War, For Whom the Bell Tolls. After the nationalist victory in early 1939, El campesino fled to the Soviet Union. First warmly welcomed, he soon got into trouble because of his outspokenness and independence. Sent to slave camps, parts of the Gulag network stretching over the whole of the Soviet Union, he was able to escape to Iran as a result of a series of extraordinary circumstances, including a major earthquake in Ashgabat in Turkmenistan. In Paris he bore witness in a trial about the existence of Soviet slave camps and wrote his book about the Spanish Civil War and the Gulag with the assistance of Julián Gorkin, a Trotskyite persecuted by the communists during the Civil War.

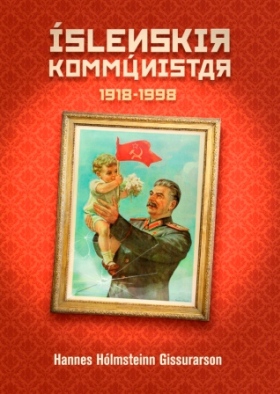

On 17 July 2016, 80 years had passed since the Spanish Civil War broke out when nationalist generals led by Francisco Franco rebelled against the young Spanish Republic. On this occasion, AB, the Public Book Club, republished the book El Campesino by Valentín González and Julián Gorkin. It is accessible online and also in print. González, El campesino, a general in the Spanish Republican Army, was often featured on the front pages of the Icelandic communist party organ Thjodviljinn, appearing as well as one of the characters in Ernest Hemingway’s famous novel on the Spanish Civil War, For Whom the Bell Tolls. After the nationalist victory in early 1939, El campesino fled to the Soviet Union. First warmly welcomed, he soon got into trouble because of his outspokenness and independence. Sent to slave camps, parts of the Gulag network stretching over the whole of the Soviet Union, he was able to escape to Iran as a result of a series of extraordinary circumstances, including a major earthquake in Ashgabat in Turkmenistan. In Paris he bore witness in a trial about the existence of Soviet slave camps and wrote his book about the Spanish Civil War and the Gulag with the assistance of Julián Gorkin, a Trotskyite persecuted by the communists during the Civil War. The book was first published in 1952 by Studlaberg in a translation by Hersteinn Palsson. RNH Academic Director Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson contributes an introduction and notes to the new edition, discussing the historiography of the Spanish Civil War. He points out that at least four Icelanders were volunteers in the Civil War (all on the Republican side), whereas only one Icelander is known to have perished in the Soviet Gulag, the young daughter of economist Benjamin Eiriksson who was imprisoned with her mother. The republication of the book forms a part of the RNH project with AECR, the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists, on “Europe of the Victims”.

The book was first published in 1952 by Studlaberg in a translation by Hersteinn Palsson. RNH Academic Director Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson contributes an introduction and notes to the new edition, discussing the historiography of the Spanish Civil War. He points out that at least four Icelanders were volunteers in the Civil War (all on the Republican side), whereas only one Icelander is known to have perished in the Soviet Gulag, the young daughter of economist Benjamin Eiriksson who was imprisoned with her mother. The republication of the book forms a part of the RNH project with AECR, the Alliance of European Conservatives and Reformists, on “Europe of the Victims”.