At the annual meeting of the Platform of European Memory and Conscience, to which RNH belongs, in Vilnius in Lithuania 28–30 November 2017 one main theme was the mass murder of Roma people (gypsies) in the Second World War where the Nazis were the chief perpetrators. The Platform was founded in 2011 in accordance with declarations by the European Council and the European Parliament that communist totalitarianism had to be condemned alongside Nazism and that the memory of its victims had to be upheld. The Platform’s first President was Göran Lindblad, who while a member of the European Council during his tenure as an MP for Sweden’s Moderate Unity Party, had been instrumental in having the declaration of the European Council adopted. At the 2017 meeting, Professor Lukacz Kaminski from Polland was elected President instead of Lindblad. Trustees of the Platform include Professor Stéphane Courtois, Editor of the Black Book of Communism (published in the Icelandic translation of Hannes H. Gissurarson in 2009), and Washington Post columnist Anne Applebaum, the author of books about the Gulag and the Iron Curtain. The annual meeting was held in the Tuskulenai Museum in the Tuskulenai Peace Garden where after the collapse of the Soviet Union mass graves were found with the victims of communism in 1944–7. The Platform’s President Lindblad laid a bouquet of flowers to a memorial to the victims in the Park. The Genocide and Resistance Research Centre of Lithuania organised the meeting, where four new partners joined the Platform, including the Collège des Bernardines in Paris.

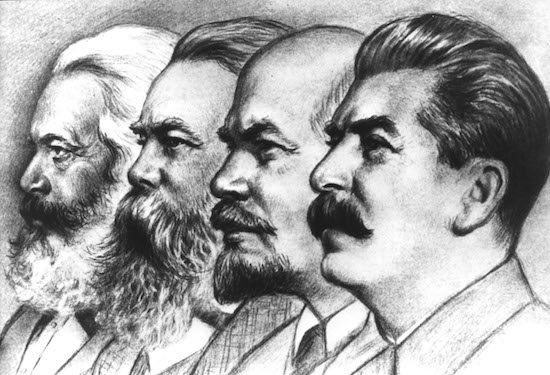

![]() RNH Academic Director Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson attended the annual meeting and gave a talk about several projects which RNH undertakes jointly with ACRE, the Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe, under the label “Europe of the Victims”. Recently, Gissurarson has been commissioned to write a report, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, The Voices of the Victims, to be published late in 2017. His argument there is that Stalinism was a logical consequence of Marxism rather than an aberration from it and that Western apologists of Soviet terror share some collective responsibility with the Soviet rulers. He briefly surveys anti-totalitarian literature of the 20th century, including the novels by George Orwell and Arthur Koestler, Nineteen Eighty Four and Darkness at Noon, and the accounts of communism given by refugees or disillusioned travellers, such as I Chose Freedom by Victor Kravchenko, Out of the Night by Jan Valtin, Under Two Dictators by Margarete Buber-Neumann, El Campesino by Valentín González, Nightmare of the Innocents by Otto Larsen, Baltic Eclipse by Ants Oras and Articles on Communism by Bertrand Russell. In the report, Professor Gissurarson also discusses the contribution of historians exposing the Big Lie, such as Robert Conquest, Stéphane Courtois, Anne Applebaum, Bent Jensen and Frank Dikötter.

RNH Academic Director Professor Hannes H. Gissurarson attended the annual meeting and gave a talk about several projects which RNH undertakes jointly with ACRE, the Alliance of Conservatives and Reformists in Europe, under the label “Europe of the Victims”. Recently, Gissurarson has been commissioned to write a report, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution, The Voices of the Victims, to be published late in 2017. His argument there is that Stalinism was a logical consequence of Marxism rather than an aberration from it and that Western apologists of Soviet terror share some collective responsibility with the Soviet rulers. He briefly surveys anti-totalitarian literature of the 20th century, including the novels by George Orwell and Arthur Koestler, Nineteen Eighty Four and Darkness at Noon, and the accounts of communism given by refugees or disillusioned travellers, such as I Chose Freedom by Victor Kravchenko, Out of the Night by Jan Valtin, Under Two Dictators by Margarete Buber-Neumann, El Campesino by Valentín González, Nightmare of the Innocents by Otto Larsen, Baltic Eclipse by Ants Oras and Articles on Communism by Bertrand Russell. In the report, Professor Gissurarson also discusses the contribution of historians exposing the Big Lie, such as Robert Conquest, Stéphane Courtois, Anne Applebaum, Bent Jensen and Frank Dikötter.